This is a blog post adaptation of the following video:

This video is part of a series called Isn’t Music Theory, where I share some of my ideas about music and how we learn it. I’ve transcribed the video and made some changes to it for this post. If you’re interested, check out the whole series on the Midnight Oil Collective YouTube channel.

Music, language, and learning.

Humans are vocal learners, which means that, in addition to being able to recognize patterns of sounds, which lots of other animals can do, we can also hear sounds and then reproduce them with our voices. It’s what we do every time we speak, and we can only do that because we’ve heard these sounds for all of our lives. There are other animals in the category of vocal learners, including bats, elephants, seals, whales, songbirds, parrots, and even hummingbirds. One thing we all have in common is that we learn songs from our parents. Those songs can be about territory or love, and sometimes they’re just social or playful.

Often when scientists talk about the human equivalent of birdsong they’re not actually talking about human song; they’re talking about language. There are cliches about music being the universal language, like this one:

Music is the universal language of mankind.

Henry Wadworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: “Outre-Mer: A Pilgrimage Beyond the Sea.” New York: Harper & Brothers, 1835. p. 4.

It turns out people in the mid-19th century didn’t really have the most zoomed-out view of humankind so there are a lot of limits to that metaphor, but there are some similarities between music and language that make it really useful to think about. One is that we’re putting sounds in order and that order contributes to the meaning. Another is that we learn language and music by listening.

Nobody really knows why we have both music and language, but there are lots of theories about why music exists. They range from the underwhelming, like that of Steven Pinker, the psychologist, who wrote this:

I suspect that music is auditory cheesecake, an exquisite confection crafted to tickle the sensitive spots of at least six of our mental faculties.

Steven Pinker

Steven Pinker: How The Mind Works. New York, W.W. Norton, 1997. p. 534.

…All the way to powerful and sweeping explanations, like the Aztec story that music was taken from the sun by the sky and the wind and brought down to the earth.

“How Music Came to the World.” Mexicolore, August 25, 2013. https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/stories/how-music-came-to-the-world

Here’s an interesting case study.

Thinking about vocal learning as learning songs from your parents got me thinking about this song that I learned from my dad that I’ve literally never heard anyone else sing. It’s this really dumb song that he taught to me as a kid, and that he actually learned from the radio when he was a kid. He taught it to me on a hike when when I was maybe eight or nine years old. When you’re hiking and you sing songs, it gets pretty wacky pretty fast, so he taught me this song that sounds like it’s nonsense, but it actually has words with meaning.If I were to write out the lyrics as they sound, it would look like something this:

Mairzydotes and dozydotes and little lamzidivey.

A kiddlidivy too, wouldn't you?

Oh mairzydotes and dozeydotes and little lamzidivey.

A kiddlidivy too, wouldn't you?

The actual lyrics are:

Mares eat oats and does eat oats and little lambs eat ivy. A kid will eat ivy too, wouldn't you?

So the song is supposed to sound like nonsense when it is in fact about the cuisines of cloven-hooved animals.

It’s actually kind of clever.

How do you transform and freeze a song at the same time?

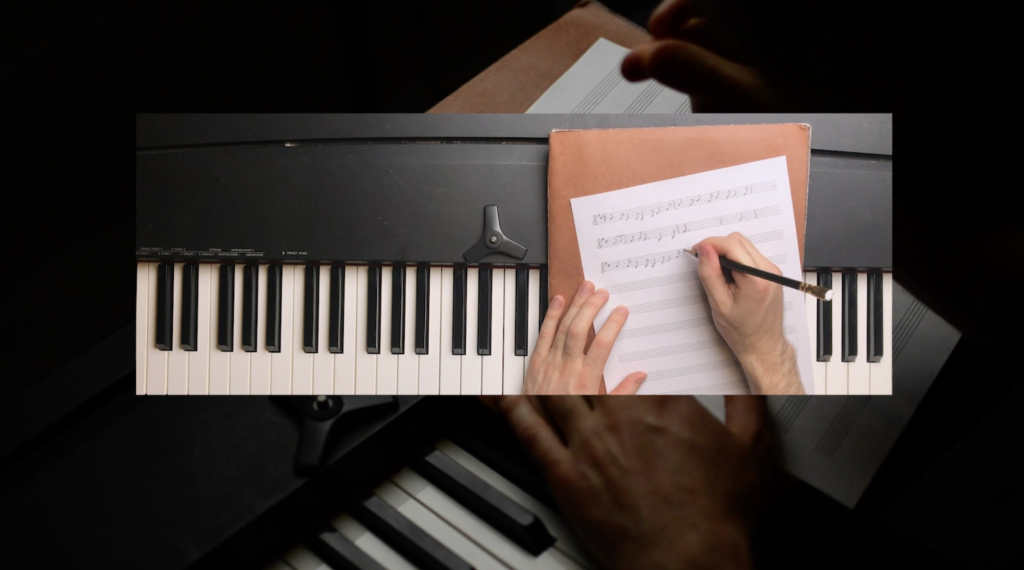

So I thought it would be fun to look this song up to see how accurately I learned it from my dad, who learned it from the radio, probably in the 50s. But before I did that I wanted to kind of freeze this song in place so that I can go back later and see how it existed in my memory. So I decided to do something that only humans do with their songs.

In fact, even among humans, only a small portion have done this with their music.

In fact, the thing I did changed the music fundamentally from a set of sounds to a set of ideas about sounds.

When I did this, the character of my voice was lost, all of the color (or timbre) of the sound was lost, all of my out-of-tune-ness went away, as did all of my subtle variations in timing. Humans started doing this at least a millennium ago, and the ability to do this has opened up wildly different possibilities for music and the relationships between music and memory. It has allowed us to think about sounds in a way that’s disconnected from the sounds themselves, for better or for worse.

What I did was this: I wrote it down.

Why do we notate music?

This is a system you may have seen where I make little marks that mean different things about the sounds’ pitch (how high or low it is) and the rhythm. I make all of these marks with reference to a set of five lines called a staff. This system has changed a bunch through time. For instance, this thing is called a “treble clef:”

It can also be called a “G clef” because the spirally part is around the note G. Originally people literally just wrote a G on the G and eventually that G morphed into this treble clef.

In addition to letting me forget about sounds I make now and still make them again later, notation also lets me come up with ideas about sounds and give them to someone else to actually turn into sounds.

This is what classical composers do.

Again, we’re talking about a lot of music, but still it’s only a very small portion of the world’s music since the beginning.

The next step in this experiment is to hear the original version of this song–the version my dad learned from. Since my dad had also not heard this song for many decades, I wanted to get him to listen too.